BLOG

What’s in the Sauce: August 2025

A source material tracker. I don’t always know how a thing will influence me until I get further down the road. This is a post to reference later, not to show off. Maybe some accountability—am I pursuing good inputs?

Guidelines: Don’t note the reasons someone else might like it. Say why I picked it up and what I’ve found interesting. How it bumped into other stuff, how it spun into something, and what I tucked away or was surprised by.

Watching

This perfect documentary, Listers: A Glimpse Into Extreme Birdwatching. (Free on Youtube!!)

One of my favorite things is listening to my brothers riffing.

Their stream of funny banter is near-constant, and this documentary feels similar. Brothers messing around! And making a beautiful interesting film. They do some really clever low-tech visual stuff that is charming. I also love the switch between camcorder footage and beautiful high-res bird shots. It feels like what I hoped the whole “everyone has a camera in their pocket!” age would spawn. Clearly, the brothers are very good at this, I’m not saying it’s cobbled together. But it has people like you could make this kind of thing energy. Probably because it’s self-distributed via Youtube. I love that they made it, I love that it’s free on their terms, I was totally engrossed the whole time.

Anne Hathaway, Robert De Niro. It was cute! It’s nice when Amazon Prime actually has a movie I’ve been wanting to watch. I’m looking for stuff to watch while sewing for my art show these days. It’s a weird thing: I’m being productive, but it still feels kinda lazy, all this screen time.

The State Theatre was showing the best Terminator, so I had to go. I had forgotten pretty much everything except that I loved it the first time. The soundtrack is really great and I need to see if it works as background office music. Arnold biking around to Bad to the Bone? Ridiculous. The 90s visual effects struck me as funnier on the big screen. Also funny? The apocalyptic future is set in 2029. Watch out for SkyNet, people.

Reading

The Overstory by Richard Powers

I snagged this from the Little Free Library and promptly stuck it in an unread stack. Then one day I was bored and trying to stay offline and I read one chapter out of context and then I started from the beginning.

Here’s the thing: the writing is beautiful. The characters are interesting. Powers’ descriptive writing style trickled into my journal entries.

Here’s the other thing: it’s super depressing to hear about trees getting chopped down all the time.

It’s a hefty book, 502 dense pages. It’s a heavy story, 8 characters whose storylines slowly merge together. I like them, I am curious about them, but I am also really bummed out by it and I might not finish it. I can only read something for so long before I need a big gust of hope, you know?

Martha Stewart’s Hors D’Oeuvres Handbook

Also a hefty tome. Martha’s birthday was August 3rd, my friend Cat and I hosted a birthday party. I used this book to make some fancy appetizers.

I love how extra Martha is. This feels like a true Martha book, written before things were super ghostwritten (though she def had help writing this one). Super comprehensive, with beautifully styled photos. This doesn’t feel timeless, but it feels good. A time capsule. And the perfect level of unhinged. Cat and I cracked up when we saw the suggestion to use a loaf of bread as a basket for sandwiches. So naturally, I made one. Worked beautifully. Martha, you genius.

Listening

Re-listening to old Home Cooking episodes in honor of the show’s new season. A total joy. I’m traveling to San Francisco to see Samin + Hrishi in conversation in September. I also recorded a voice note with my own cooking dilemma. Thinking about how projects like this need participants. The show doesn’t work unless some of us send questions. What else might I be a more active participant in? What does that back-and-forth look like for projects led by me?

Also I made Samin’s slow-roasted salmon after a podcast mention and it’s delicious.

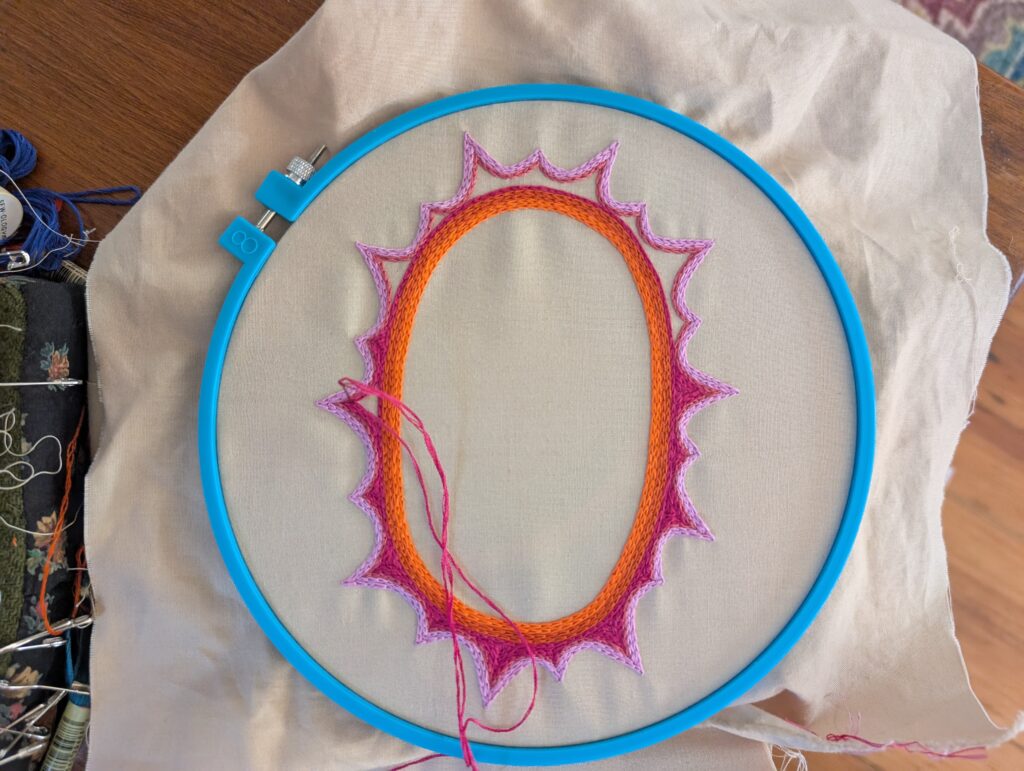

Making

What’s In the Sauce: February 2025

A source material tracker. I don’t always know how a thing will influence me until I get further down the road. This is a post to reference later, not to show off. Maybe some accountability—am I pursuing good inputs?

Guidelines: Don’t note the reasons someone else might like it. Say why I picked it up and what I’ve found interesting. How it bumped into other stuff, how it spun into something, and what I tucked away or was surprised by.

Thinking about this because I’m ramping up output as I create art for a solo show this December. My inputs spills into the work I create, so I’d better be taking care with what goes in!

Books

Amish Crib Quilts from the Midwest

Do I need to visit the International Quilt Museum in Lincoln, NE? Thinking about interactive displays, and I’d like to see how they approach it. Coziness as the vibe. Cozy but some prickliness. It’s not all sweet.

The Mountain in the Sea

It took me maybe three chapters to get into this, then I was hooked. I like a weird book. Consciousness, language, octopus civilization, an AI being, a person trapped on an autonomous slave ship. It’s a wild list. Read because Robin Sloan recommended it.

Margo’s Got Money Troubles

I picked this up because of the 2025 Tournament of Books. (Also a Sloan mention. I find a source that resonates and keep trusting it! For a long time, that was Austin Kleon, but he blogs less now, and his Substack isn’t quite the same energy.) The book itself was zippy, and interesting, but not one that I wanted people to read so I could talk about it, the way I feel about The Mountain in the Sea.

Art

I love these frames + photos by artist Gabe Schneider. The ones with video inside the frame (swipe to slide 3) feel extra special to me. Usually I’m kind of a video skeptic, and then I see a thing like this and want to try my hand at it.

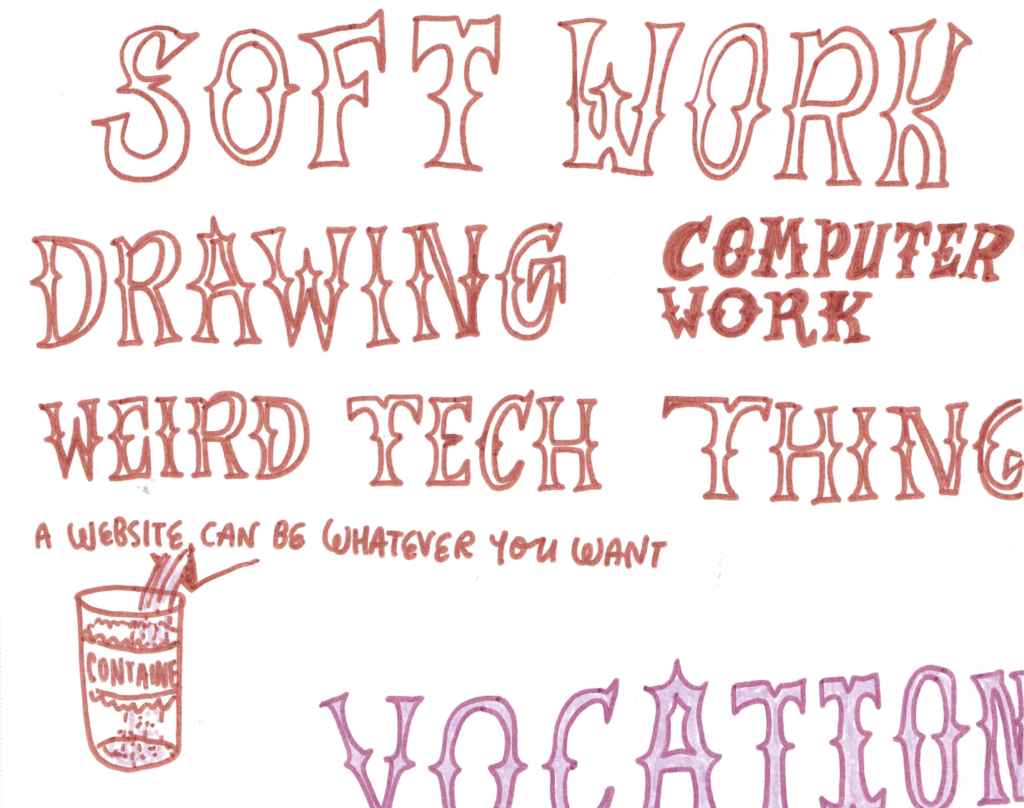

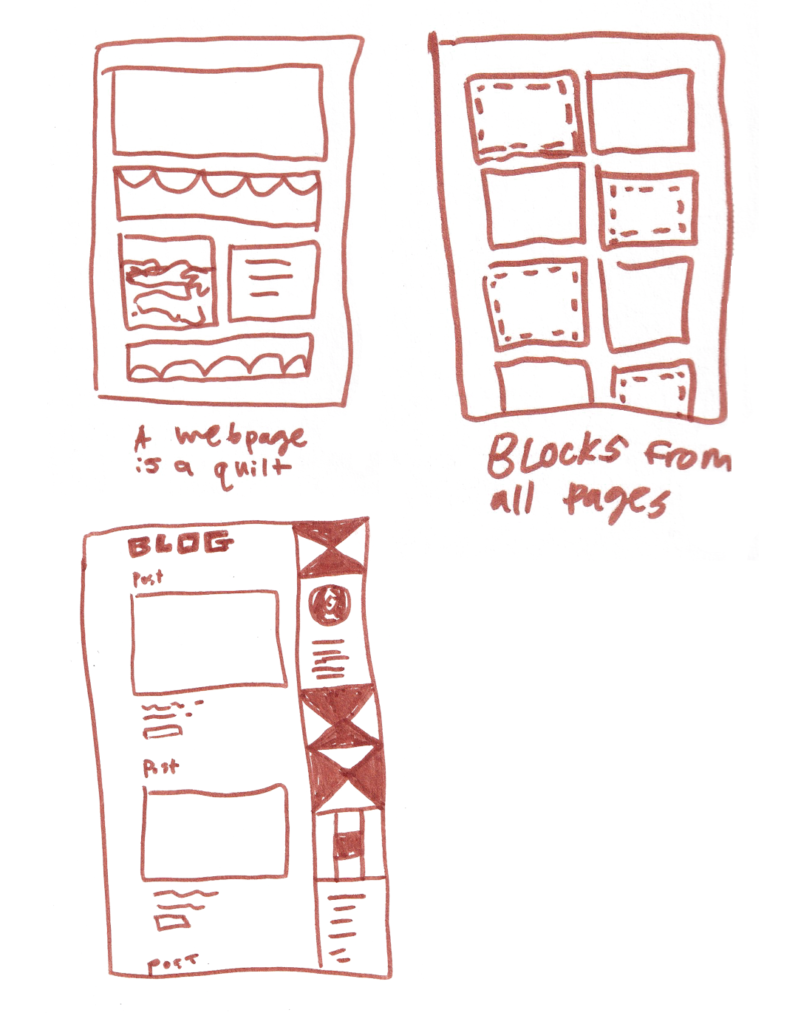

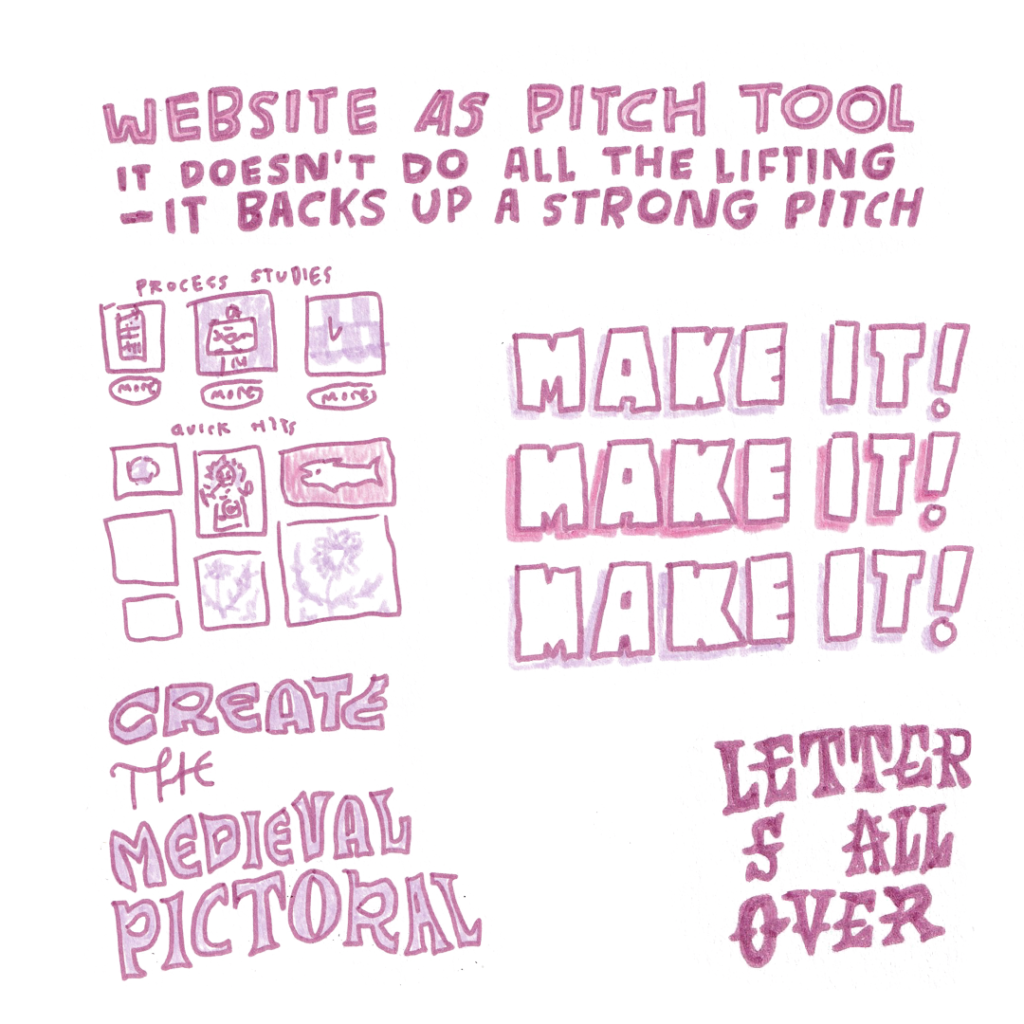

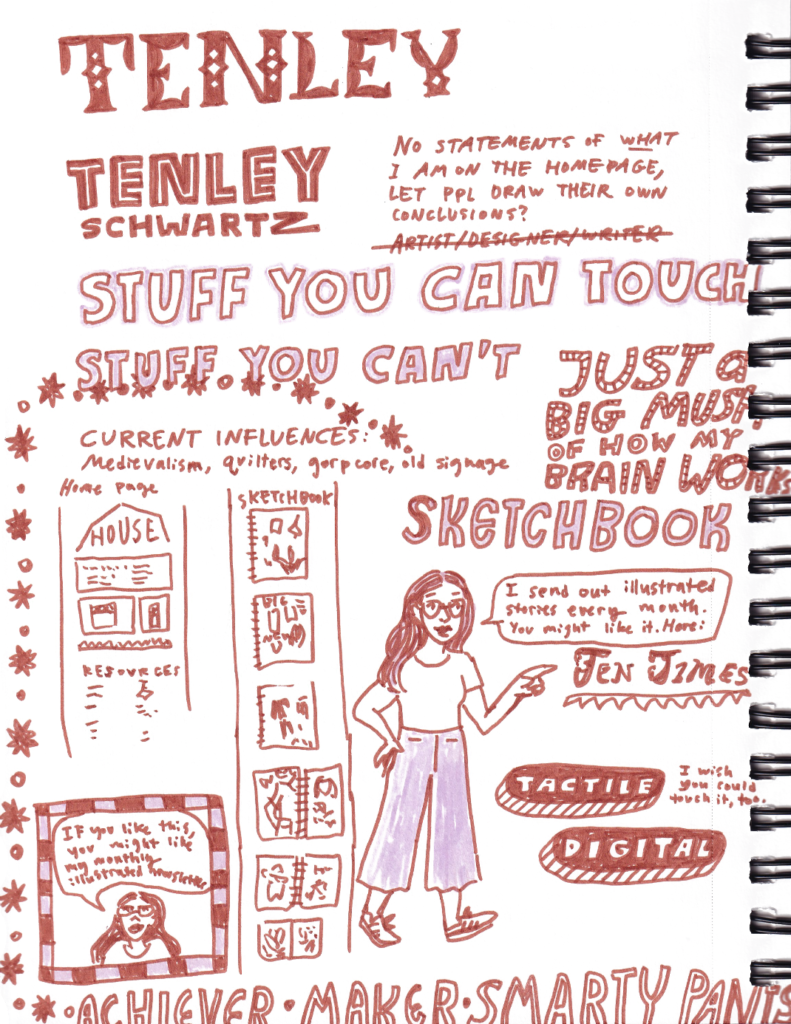

A Website Can Be Whatever You Want

I wanted my website to be a container shaped to fit my very tactile sewing and drawing practices.

I’ve been curious about building my own thing for a while, but found it daunting. Did I have to learn HTML? What about CSS?? My only programming experience was a semester where I created a clunky Python game.

My former portfolio site was a ‘custom’ template cobbled together on Wix. It functioned fine as a record of work when I was applying for jobs, but it wasn’t very exciting.

With my job switch, I was around a lot more designers, and they were building websites with these drag and drop-ish platforms. Suddenly, it seemed more possible to do myself. My coworker recommended Elementor, which is built on top of WordPress for a ton of functionality. It was the perfect amount of ease and customization for my graphic-design-heavy skillset.

Now, the site is a home base for my creative practice, a place I’m proud to have people looking at when I apply for artist residencies or gallery shows. It has a prettier blog layout so that my own writing has a nice place to live. I’m excited to keep messing with it.

Headers are set in Sloppy Medieval, a custom font made by me.

I traced my letterforms with Adobe Illustrator, converted them to a font with the Fontself extension, then used Fontie to create the webfont files.

It’s meant to be charmingly wonky.

It feels powerful to have this much control of my website!

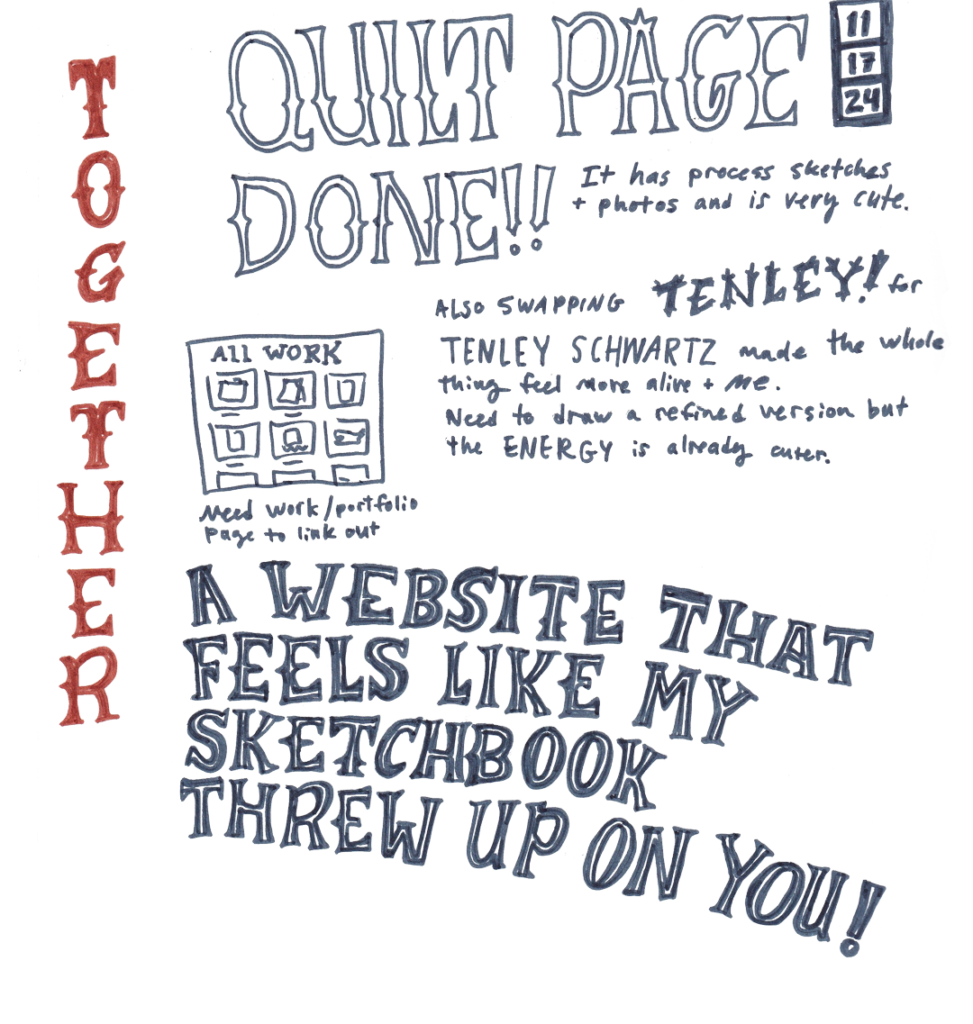

Here are some notes on the process from my sketchbook:

Stories in Place: A Midwest Syllabus

I’ve been thinking about what it means to belong, specifically in the midwest, for years. I think I could probably teach a class on the topic. Here’s what I’d put on my syllabus. I’d recommend them even if you’re not cosplaying higher ed.

Dancing with Welk: Music, Memory, and Prairie Troubadours by Christopher Vondracek

This book feels honest. It’s hard to write about a place that so easily becomes the butt of jokes. To write without treacle-y sentimentality and without harshness towards an isolated place. This book is about searching–for some kind of meaning or vocation or belonging. For wondering if you can make it, for not knowing who you are exactly, for following the thread of a publicly-loved but critically panned musician who specialized in accordions.

It’s about all kinds of things, and it feels familiar.

In the small town-iest twist, this one happens to be written by someone from my own hometown. I’m pretty sure my dad painted his parents’ house.

An excerpt, one of many starred and underlined passages:

“As I listened, about how writing about rural South Dakota means being authentic, about roots, about how you can’t just have some east coast carpet-baggers coming in and pointing at our taxidermy on the walls of the dentist office and calling that an observation, I felt my whole body go rigid. One of the session leaders got chills in the back of his neck when he proclaimed, “I saw the band march past last week and only thirteen kids, maybe three lines, a banged-up snare drum, no one was in step, and a feral cat following behind, but, darnit, we had a band.” And I thought of my dad, who taught at a small school, but who also asked kids to wear clean spats, who asked that kids shine their horns, who asked that kids stay in line, and march in step, tighten the snare, keep dents out of the tuba, even with the school soon closing after the farm crisis, even with the ceiling tiles leaking. “A tuba’s the price of a good used car,” he said to guffaws. “I’m serious.” Sure, as a rural child, I knew the slam of the locker on the weekend when the gun show took over our school, when ten thousand firearms and arrowheads and collectible coins assembled in our hallways and gymnasium. But I also knew how my classmates urged me to play the piano in the gymnasiums in the morning, how sometimes our middle school choir teacher, to quiet the class, would send me to the front to hear the rubbery bass hand of Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus & Lucy.”

Dakota: A Spiritual Geography

By Kathleen Norris

Read this one for the observations about insiders and outsiders in tight-knit communities.

I held this one close as I wrote a senior project on belonging in my final semester of undergrad. My project advisor, Dr. Jenny Bangsund, recommended it as one that had helped her understanding of the place when she moved to the area.

“It is a trusim that outsiders, often professionals with no family ties, are never fully accepted into a rural or small-town community. Such communities are impenetrable for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact that the most important stories are never spoken of; the local history mentality has worn down their rough edges, or placed them safely out of sight, out of mind. To learn the truth about the web of close-knit families that make up an isolated small town on the Plains, one must look back some years, to the men and women of the homesteading and early merchant generation. By now they’ve mostly been mythololgized into the stern, hard-working papa and the overworked-mother-who-never-complained, all their passions and complexities smoothed over. But many of these people, the women especially, had an intense love/hate relationship with the Plains that lives on in their children.”

The Peace of Wild Things

by Wendell Berry

At this point, so many people I enjoy, admire, or love are fans of Wendell Berry that I’ve been forced to pay attention! Poems were my way in, and are still my favorite, but I like his essays, too. There’s a lot in here about the dignity of sticking to a place and stewarding it. And about the nourishing ways we get tied together in community.

A small place never feels unworthy, in Berry’s world. Repair is valued work, and doing it matters, no matter what rages outside your small plot.

XXII. (from Sabbath Poems) There is a day when the road neither comes nor goes, and the way is not a way but a place

Let’s throw in an essay, too.

from Conservation is Good Work:

“The concepts and insights of the ecologists are of great usefulness in our predicament, and we can hardly escape the need to speak of “ecology” and “ecosystems.” But the terms themselves are culturally sterile. They come from the juiceless, abstract intellectuality of the universities which was invented to disconnect, displace, and disembody the mind. The real names of the environment are the names of rivers and river valleys; creeks, ridges, and mountains; towns and cities; lakes, woodlands, lanes, roads, creatures and people. And the real name of our connection to this everywhere different and differently named earth is “work.” We are connected by work even to the places where we don’t work, for all places are connected; it is clear by now that we cannot exempt one place from our ruin of another. The name of our proper connection to the earth is “good work,” for good work involves much giving of honor.”

I’d pair the Conservation essay with Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing. Odell’s book leans in to using ecological terms, the same ones that Berry describes as ‘culturally sterile.’ Odell writes about getting outside of the social media tension loop, which plays nicely with Berry’s monklike refusal to adopt new technology. Their differing approaches and underlying philosophies have an interesting friction that would make for lively class discussion. (or a book club reading–anyone??)

Boom Town

by Sam Anderson

Wildly funny, engaging, and surprising.

This one is assigned as much because it’s a treat to read as for the ways it peels back the intense ways people morph their place or are themselves warped by it. You have self-serving city officials, basketball players borrowed from other hometowns, diligent weathermen, rockstars that never moved to LA, and a perfect essay about James Harden’s beard.

It’s a brilliant picture of how any place is interesting when you (or, in this case, a brilliant journalist) pay close attention. That’s at the forefront of my mind in any midwest discussion. Pay attention to your place.

From Boom Town:

“The city conducts itself, whenever possible, like a hiker threatened by a bear in the woods, hysterically exaggerating its size.”

“Bring the young people back,” he had said. “Young people are like salt and pepper. They cause trouble, yes, but they also bring excitement.” Young people, however, are not spices that sit around waiting on racks. They are not folding chairs. They are sentient and unruly, and they tend to be drawn to specific stimuli: change, danger, glory, and–above all–other young people. All those things were now absent from Oklahoma City.”